We bring our past into the present

Our Museum exhibits and display area focus on three major themes: Coal, Coke, and Community. The Museum will be closed to all visitors starting July 2023 and will remain closed through the 2023-2024 academic year.

Coal—Nature's Black Diamond

The Pittsburgh Coal Seam was once recognized as being the most valuable coal bed in the bituminous coal fields of Pennsylvania. The seam crops out at Pittsburgh, thus the Pittsburgh seam is one of forty-two distinct coal beds in the state. No other bituminous seam in Pennsylvania approaches this seam of coal in its overall excellence as a metallurgical coal, which set the worldwide standard. This bed is estimated to have originally contained more than ten billion tons of coal.

The map on the right shows the region known worldwide for “Connellsville Coke,” a portion of the Pittsburgh seam unsurpassed for beehive coking. This remarkable coking coal occurred in a limited area, tucked along the base of the Laurel and Chestnut Mountain Ridges, extending from a point near Latrobe and moving in a southwesterly direction through Westmoreland and Fayette Counties, ending near Smithfield, a distance of nearly forty miles. Located within fifty miles of Pittsburgh, it was the coal that made the coke that made the steel that spurred the industrial expansion of the United States.

The purity of the Connellsville coal bed, as well as its chemical and physical characteristics, made it particularly adapted for coking. The earliest beehive ovens were built in the area surrounding Connellsville before 1845. The coke that was produced from this coal vein was almost 100 percent pure carbon. Connellsville coal was used as run-of the mine coal in the blast furnaces of Pittsburgh without any need to wash it to remove impurities often present in inferior grades of coal; nor was there any need to sort or crush it before the coking process. Chemically speaking, Connellsville Region coal had a low percentage of ash and phosphorus and its sulphur content was less than 1 percent. Being almost entirely free from slate, or other blemishes, no other bituminous seam in Pennsylvania approached it in overall excellence or could compete with it in “cheapness” of production. The seam was of a consistent thickness (7–15 feet) and uniform in quality, remarkably soft, and of superior chemical composition. A 1-foot acre from this area of the Pittsburgh seam was equal to 1,500 tons of coal.

Other coal seams located within the Westmoreland and Fayette County areas include the Waynesburg, Uniontown, Sewickley, and Redstone. These seams, along with the Pittsburgh seam, provided multiple uses: domestic and industrial heating, steam coal, and gas coal used to produce illuminating gas. However, nearly all the coal produced in Fayette County and Southern Westmoreland County was made into the world famous, Connellsville coke and used in the regions steel industry. It earned the reputation as the standard coking coal of the world.

Coke Making

Coal had been mined for many years before the idea of making coke in beehive ovens became popular. Coke is the bones of coal. In a general way, coke is as near a pure carbon as may be had; as near an uncrystalized diamond as can be made. The beehive coke oven transforms the soft, crumbling bituminous coal into a hard, porous substance which will “stand up stiff-backed” under a ponderous load of iron ore and limestone in the blast furnace, where coke is chiefly used. As early as 1860, Connellsville Coke was used exclusively in Pittsburgh’s first successful blast furnace, the Clinton Furnace, and became the benchmark against which all other cokes were measured.

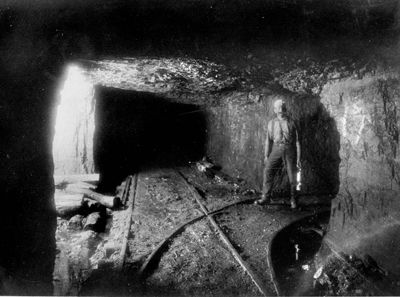

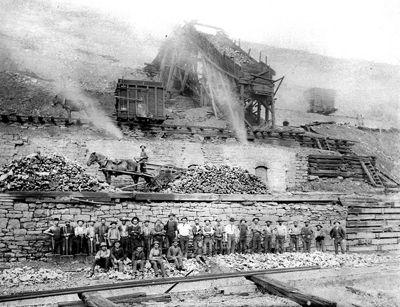

The process of coking is simple, but requires expert care. The shovel never touches the coal from the time it is loaded into the wagon down in the bowels of the earth until it is raked out of the oven in the form of coke, hot and smoking. The coal from the mine is taken from the coal tipple in larries [lorries]; a larry-load fills one oven. The larry travels along a track over the top of the long double row of ovens and drops its load into each through the circular hole in the roof known as the trunnel head. Then the opening in the oven front, measuring about two feet square with an arched crown, is bricked up and plastered with clay, leaving a space for sufficient air to get in the oven, a width of approximately 2 inches (usually measured quickly by the width of the coke makers’ three fingers). The heat in the oven from the last burning fires the fresh load of coal, and then there is nothing to do but let it sizzle while regulating the heat so that the coke does not roast too slow or burn too fast, by enlarging or daubing up the space left for draught. The temperature of the brick interior averages 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit. The object in baking the coal is to consume as much of the volatile matter (tar, gases, light oil) as possible without consuming the fixed carbon. This is where the coke-maker’s trained eye and judgment comes into play, as he notes and governs the progress of the process according to the tints of the delicate, shimmering flame that dances over the glowing mass. When it has the proper color, and is done, the “drawer” turns the hose on it drenching the load with 850 gallons of water to cool the oven, so that the coke can be handled with the drawer’s long, heavy singletoothed iron rake. Then, there is nothing more to do but fork the light steel-gray product into a railroad car and it is ready for shipment via railroad. The usual conversion period was 48 hours, but on weekends, 72- hour coke was made since Sunday was not a workday. Each worker usually was assigned six ovens so that he would draw three ovens a day. Usually it took about 2 hours to empty each oven.

The Coming

Learn a little about the early days of the coal and coke region in the excerpt from Patch/Work Voices: The Culture and Lore of a Mining People.

In the eighteenth century, groups of English, Welsh, Scotch-Irish, and German settlers crossed the Alleghenies and settled at the foot of the mountains. They hunted, fished, and farmed the land, and they tamed it. They built their towns—Beeson Town (later Uniontown), Connellsville, Brownsville. They lived off the land and the earth waited. Industrial growth came to the area via its transportation network—the National Road, the Youghiogheny and Monongahela Rivers. Iron ore was discovered and iron furnaces sprang up.

And the people diversified.

They farmed and mined and smelted. The Civil War came and went, and industrialization became a powerful force. Power was needed for the machines. Stronger materials were needed to make the machines, and the earth waited. The early inhabitants of the area farmed, mined iron ore and smelted, but coal was in the earth. Coal was a form of power and the earth became restless. Some decided to use the earth’s power and to mine its coal, not for domestic purpose, as early families in the area had always done, but for industrial purposes. It was discovered that this coal, the coal of the Pittsburgh seam, particularly in the Connellsville region, was extremely good for coking and steel making.

And so it began.

To relieve the earth of its coal, people were needed, and the original inhabitants were too few in number for the largeness of the task. The word went out, and the migration from the corners of the Western world to this area began. It was a migration which would take decades for completion and which would bring together an array of differing peoples.

They came.

They came here, from the late 1800s on, for a variety if reasons—to be with families, to provide for the necessities of life, to ensure better social conditions, but above all they came because of a need, because of a desire for better economic opportunities for themselves and for their families. They came—more English, more Welsh, more Irish, more Scotch, more Germans. They came—the Slovaks, the Poles, the Yugoslavians, the Russians, the Hungarians, the Ruthenians, the Italians, the Blacks. They all came to work within the earth, and they stayed.

Through the years these people adapted to a new existence and, in the process, produced a culture, which was a unique blend of ethnic and industrial attitudes, customs, and practices of both Europe and America. Their lives have become a part of the history of the bituminous coal industry, and it seems only fitting that an attempt be made to chronicle a few of their stories.

And so the earth and the people—of necessity—came together here in southwestern Pennsylvania. The people mined, they lived, they fought, they laughed, they struggled, they died, and they preserved in this land.

—Patch/Work Voices: The Culture and Lore of a Mining People, 1977.